Avoid these AI coding mistakes

The mistakes we've made using tools like Cursor and Claude Code and how to avoid them.

Do AI code editors actually make us better? We asked the product engineers at PostHog and the response was mixed.

Some find autocomplete great, but need to rip out anything beyond that. Others find they’re a huge speedup, but only in specific circumstances.

Everyone agreed on thing though: coding with AI is a skill. It takes practice and a lot of mistakes to get good at it.

We know this because we’ve made a bunch of mistakes over the past few years working with these tools, building AI-powered features, and working with companies in the space.

Here’s what we’ve learned.

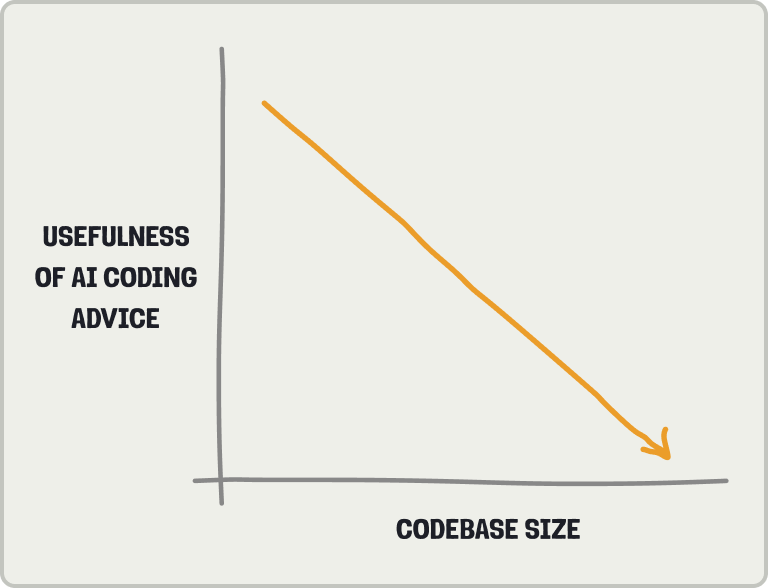

1. Treating your big codebase like a small codebase

Like many “real” companies, PostHog’s codebase is big: 8,984 files and 1,623,533 lines of code, to be exact.

Sadly, most of the AI coding advice out there isn’t written for this scenario. It’s written for new developers vibe coding from zero to one, and that advice doesn’t work when you’re working with a large, existing code base.

Although it’s less sexy than vibe coding, being thoughtful about using AI is more important in a larger codebase for the following reasons:

Less of your app fits into the AI tool’s context windows, which means you need to be more careful about what goes into it. This is true of both coding and building AI-powered features.

AI can go and make changes to parts of your apps you don’t expect. Radically changing the UI might be fine in a small prototype, but it can ruin a lot of things in a big app like ours.

Tests, linting, and type checking increase in importance as they help protect against AI making changes with unintended consequences.

Be specific with your prompts. In a larger codebase, individual files and features can take over your context window. Vaguely asking “make it better” will leave the agent confused and ineffective.

As one of our product engineers, Paul D’Ambra, noted in a blog on how he uses LLMs:

They’re not actually very good software engineers… particularly since most of the data they’ve ingested about software engineering is “blogs on how to start something from scratch”. So, if that’s not the task. Then I find it often harder to prompt an LLM to do than to do it myself

2. Not providing the right context, rules, and guardrails

DO NOT GIVE ME HIGH LEVEL SHIT, IF I ASK FOR FIX OR EXPLANATION, I WANT ACTUAL CODE OR EXPLANATION! I DON’T WANT “Here’s how you can blablabla” -

posthog/.cursorrules

As LLMs are non-deterministic, they can go off the rails in a lot of ways. You need a structure in place to keep them on track.

Our AI install wizard is basically a big scaffold to do just this. Users could ask AI to install PostHog for them, but would quickly start using out-of-date patterns, hallucinated API keys, and phantom libraries. By providing context on PostHog along with guardrails for implementing it, the wizard prevents all of this.

Unfortunately, these are rarely set up for you. You need to do this yourself. To help, here are some context, rules, and guardrails we rely on (and recommend):

Reference examples of code already written whenever possible, such as pre-built UI components, database schema, optimized database queries, testing patterns, and state management structures.

Documentation, source code, and examples for the libraries, frameworks, or tools you are using. Danilo calls LLMs “a delayed, lossy, compressed snapshot of the web” so this ensures they have as complete of a picture as possible. We added “Copy as Markdown” buttons to all our docs pages to help with this.

.cursor/rules. Have different rule files for different languages (like Python, Typescript, and Rust). Include principles, project structure, dependencies, best practices, naming conventions, logging, testing, and security details.claude.mdand other specification files. A lot of what to include here overlaps with.cursor/rulesbut having clear spec of what you want to do matters a lot more as well as commands Claude can use for tests, linting, and building. See ours here.Subagents for Claude to help with specific tasks like code reviews, systematic debugging, test writing, and prompt engineering. For example, some of our team use a combination of Claude and Mergiraf to resolve gnarly merge conflicts.

Of course, engineers have built a whole set of non-AI (😱) tools for preventing mistakes and issues. These work just as well (if not better) with AI, and upgrades to these tools often have a bigger impact on developer productivity than AI tools do. Examples for us include:

Ruff, Oxlint, mypy, Prettier, and more for linting, formatting, and type checking.

Jest, Playwright, pytest for testing.

Type hinting required in both Python and Typescript.

IDE tooling like PyCharm, JetBrains’ testing suite, and IntelliJ.

Style guides and coding standards.

Developers, especially product engineers, were already relying on tools like these prior to AI. AI has just made these deterministic checks and guardrails even more important.

Like AI, the rise in importance of these tools isn’t expected to slow down either. As Gergely from Pragmatic Engineer says:

Google is preparing for 10x more code to be shipped. A former Google Site Reliability Engineer (SRE) told me:

“What I’m hearing from SRE friends is that they are preparing for 10x the lines of code making their way into production.”

If any company has data on the likely impact of AI tools, it’s Google. 10x as much code generated will likely also mean 10x more:

Code review

Deployments

Feature flags

Source control footprint

… and, perhaps, even bugs and outages, if not handled with care

3. Trying to use AI on something you know it’s not good at

Claude Code writing Rust is a

whileloop that accelerates climate change - Nick Best, Team Ingestion Product Engineer

Using AI most effectively requires piling up a collection of examples of situations where AI is and isn’t useful. You can waste a lot of time and energy repeatedly asking it to do something you know it can’t do.

A helpful way to remember all of this is anthropomorphizing your AI assistant like it’s a coworker. Some call AI “an army of interns” while Birgitta Böckeler settles on giving it the specific characteristics of being “eager, stubborn, well-read, inexperienced, and won’t admit when they don’t ‘know’ something.” Anthropomorphizing your AI is basically the AI age’s version of rubberducking.

Once you’ve anthropomorphized your AI, you can get specific with the situations it excels at. For our team, these include:

Autocomplete. Everyone loves hitting tab repeatedly to get their work done.

Adding more versions of tests and fixing them.

Using it for rubberducking. Asking deep questions, learning more about the codebase and context. It’s easier to understand any file or function with an LLM.

Doing research. This is not necessarily a coding-related task, but something engineers still need to do for you. No more Googling for StackOverflow answers.

On the other side, our team finds AI sucks at:

Writing code in a language it is unfamiliar with, like our internal version of SQL, HogQL.

Using the correct (or even existing) methods, classes, libraries. It regularly hallucinates these and assumes their functionality based on their name (rather than their contents).

Following best, up to date, and existing practices. It often uses deprecated APIs for example.

Writing tests from scratch. Paul says there are so many bad examples of tests out there that LLMs often churn out the same bad tests.

Identifying what AI is and isn’t good at also helps you at a meta level. It stops you from falling into the pitfall of doing easy things AI can do instead of the hard (and important) things that maybe it can’t.

4. Being content with your existing workflow

A personality trait of a great product engineer is that they are always experimenting. When it comes to AI tools, this is no different.

Our team is always testing (and talking about) new tools and approaches. There are 1,104 messages with the word “Cursor” in our Slack, 187 with “Claude Code.” This started early and is led by our cofounders.

James is an avid vibe coder, (in)famously building a prototype of our job board on a flight (before it was completely rewritten by the website team 🙈) while Tim is a real developer™ and regularly contributes mild to hot takes on AI workflows:

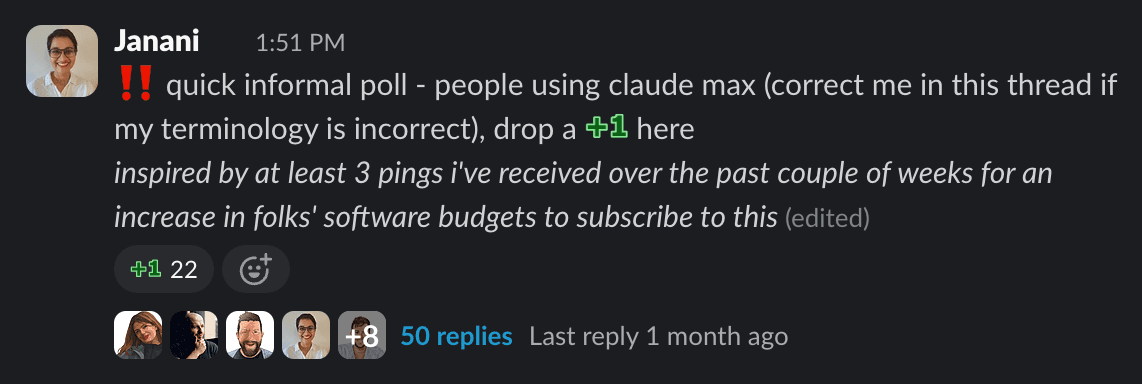

Beyond founder mode, what are some specific ways we aim to improve our workflows?

Raising our AI tool budget to $300. This enables people to try Claude Max and other top tier models.

Testing different tools, agents, and frameworks like Claude Squad (which didn’t work), Git worktrees, Traycer, Relace, Robusta, and more.

Trying different models with the same tools to figure out which models are good at what. For example, a lot of our engineers find switching to Opus extremely beneficial (over Sonnet) and have been experimenting with Qwen in Cursor.

Building and dogfooding our own AI engineering tools like Max AI, the PostHog MCP, and LLM analytics. This also means we talk to a lot of teams on the cutting edge of AI engineering like Lovable and ElevenLabs.

Nearly every hackathon has had AI-related projects being built in it. This gives more of the team opportunities to explore new tools and understand what AI is good/not good at.

At a more granular level, great engineers are always experimenting with different prompts and references. They are constantly judging the output of these to create the ideal workflow that works for them (this never ends).

5. Not using AI (at least a little bit)

Even if you dislike AI personally, it is a mistake to not use it for two reasons unrelated to you:

Your competitors are using AI. Customers will be comparing your product to AI-powered alternatives. The engineers of (good) competitors will also be trying to use AI to out ship you. You need to know what makes you product and process better than an AI-powered alternative.

Your users are almost certainly using it. They have AI in their workflows. Some of them will try to fit what you’ve built into those workflows. Especially if you are building for developers, you won’t understand the full experience of using AI in software development if you don’t try it.

In both cases, knowing the capabilities and limits of AI is helpful, and there is nothing that beats hands-on experience. In this way, coding with AI can provide huge benefits even if you use none of the code it writes.

6. Letting AI do everything for you

Because AI can seemingly do anything you ask of it, it is tempting to let it do everything. For example, we’re seeing an increasing number of people use AI tools to answer questions in live job interviews (yes, we can tell and we’ll fail you if you do it).

Ultimately, you are responsible for the end product of what you create. This is true whether you use AI or not. For nearly all work, using AI exclusively is probably a bad idea. As I’ve said before, you can’t one shot your way to a billion dollars.

AI is reshaping software. As model capacities and adoption increase, more and more of software (and software development) will be reshaped. What’s important as an individual isn’t using AI for the sake of it, but, like everything else, understanding it and fitting it into how you work.

Getting big architecture decisions right, figuring out what to build, positioning correctly, and choosing the right tools will all remain important, but it also remains up to you to figure these out, with or without AI. If you do choose to use AI, avoiding the mistakes here will help improve your odds that you’re successful.

Words by Ian Vanagas, quote misattribution aficionado.

🦔🤵 Jobs at PostHog

Want to help us make more mistakes we can learn from (or just make use of our AI coding budget)? We’re hiring product engineers and more specialist roles like:

Developer who loves teaching (write for this newsletter!)