How to design your company for speed

It's a hell of a lot easier to just be first

Welcome to Product for Engineers, a newsletter created by PostHog for engineers and founders who want to build successful startups.

Since PostHog’s first line of code on January 22nd, 2020, we’ve shipped:

SDKs for all the above

A basic CDP to stream data to warehouses

Data warehouse MVP

A wildly extensive website

...and those are just the things that worked.

We’re ingesting 10s of billions of events each month. 10s of thousands of companies rely on us. And we did all this with a team of just ~35 people. How?

The answer is simple: we deliberately designed our company for speed. You can too.

This week’s theme is: How (and why) we ship really fast

1. Don’t let designers dictate to engineers

Why? Because:

Over indexing on design polish reduces speed

The best engineers want freedom (and will probably quit if they don’t get it)

As we grew, we realized that engineers can design the UX of a product, especially if we hire people that have this skill set and provide a framework for their work.

We invested considerable time getting our design system up and running, and worked with a designer to get it done. Then we moved into a "no design by default" phase.

Had we been in this phase from the beginning, the app would have been very inconsistent... at best.

Today, we have people that can help engineers with design, but they are very happy to work reactively and fast – and they don't block work during QA.

This means we do ship work where the design isn't perfect, but we won't drop things that are important, and will keep improving them.

Further reading

A quick guide on creating a design system – Andrew Coyle

Design Systems 101 – Nielsen Norman Group

2. Product engineers > Product managers

The responsibilities of a product manager still exist, but our engineers:

Talk to users.

Decide what to build within their product.

Often pitch or build entirely new products to extend the platform.

In other words, they’re product engineers who are product-minded and autonomous, rather than mindlessly completing tickets. We have one product manager who steps in reactively if a small team needs more support.

The above requires a lot of context setting from the company. To that end, we're unusually transparent. There are two main ways we do this.

i) We make clear what we're trying to achieve.

To do this, we have a clear, simple mission and strategy. We communicate this repeatedly through our public handbook, during everyone's onboarding, repeatedly in our all hands, and when we plan each quarter of work.

We’ve refined our mission and strategy as the company has progressed. We've gradually gone from something hypothetical to these things feeling like an obvious label for what we do.

ii) We share all our metrics

We constantly update everyone on our progress towards these goals (for each product and in total), financial information, fundraising progress (before, during and after it happens), and pretty much anything else people ask for.

Further reading

How to run a transparent company – James Hawkins

3. Hire for autonomy

I think 90%+ of a company’s problems are solved by hiring the right people for your company.

When optimizing for speed, this means hiring for people who can have a big impact while working largely autonomously.

We find it invaluable to pay people during our hiring process to do some actual work. We've refined this down to a one-day task, which gives us a good sense of how much someone can get done and the quality of their actual code.

We tend to hire people with more experience, who we find work better with more autonomy. This is the magic combo when you're an all remote company, though we're working on ways to get better at growing people who are earlier in their careers.

Further reading

Everything we've learned about hiring for startups (so far) – Andy Vandervell

4. Create “mini startup” teams

I went to a superb talk by Jeff Lawson, who runs Twilio. He described how the greatest innovation at Amazon was that it felt like thousands of small startups.

Put simply: a startup gets more done per person than a big corporate, which is why PostHog works like a group of startups with lots of small teams.

Each of our products has a team of up to six who can ship with minimal interference from the rest of the company.

They:

Own their pricing.

Make their own product decisions.

Have access to the revenue, hosting, and staff costs for their product.

Are responsible for coordinating with our marketing and growth teams.

We hire a lot of former technical founders to help here.

Further reading

Jeff Lawson on management by small teams – Fast Company

5. Prioritize hiring builders over non-builders

It's simple, but if you have lots of spending and focus outside of engineering, you won't get as much built.

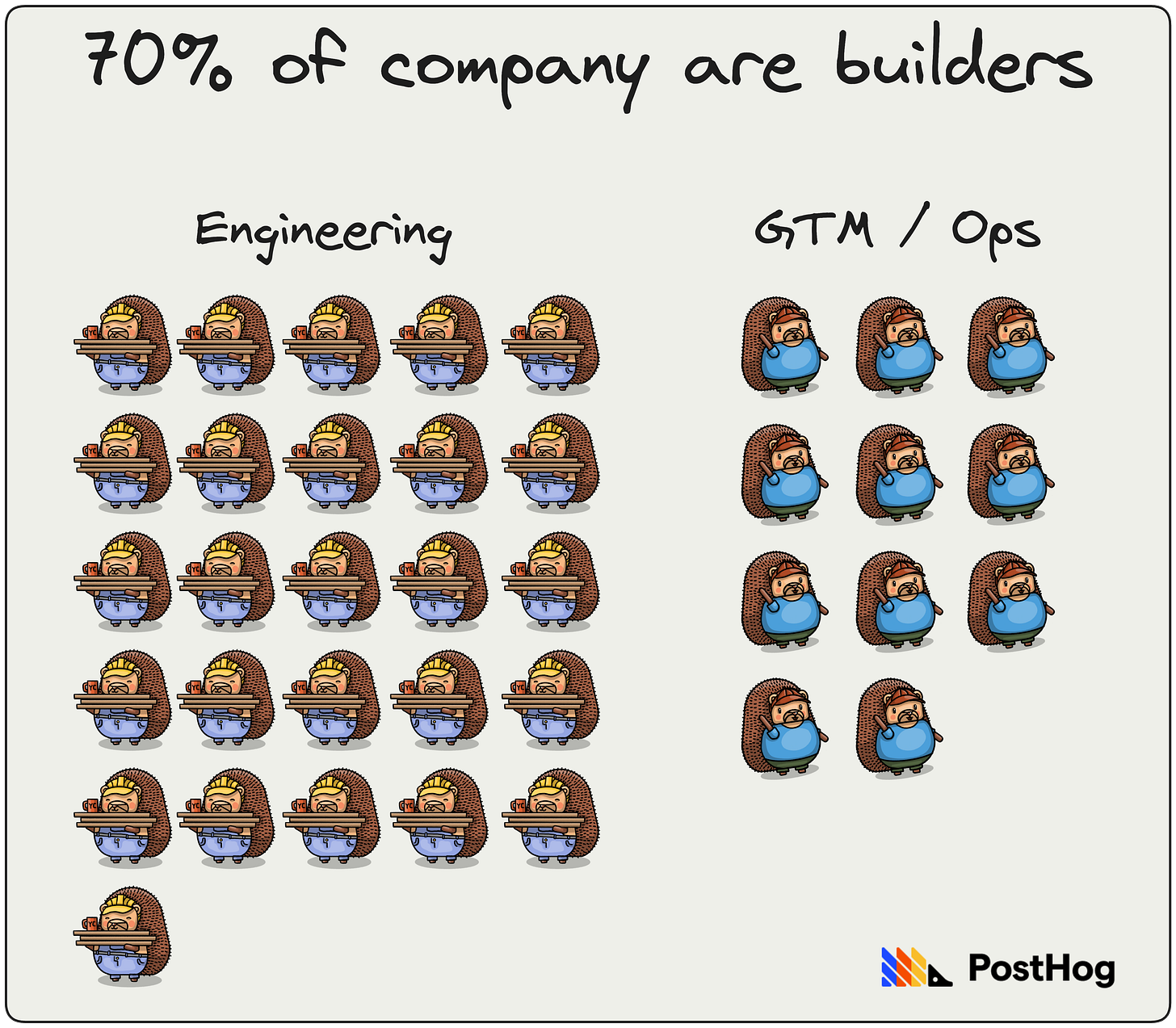

At the time of writing, we are 37 people, only 11 of whom are in Go To Market or Operations roles (and 6 of those 11 have at least some engineering in their background).

We don't do outbound sales, our marketing team is very small, we only have one product manager, and our exec team is only 3 people. These things are all by design.

We're product-led because our ideal users, engineers, want to try something rather than sit on a call.

6. Adopt the maker’s schedule

We want a culture where people can deep work.

Tuesdays and Thursdays are strictly meeting free and we push back on unnecessary meetings.

If a meeting is booked for 45 minutes but frequently only takes 25, we'll rebook it so it's shorter by default.

We have learned, often painfully, that some meetings are necessary, but we default to asynchronous communication and adapt where needed.

7. Trust and feedback over process

This is one of our core values.

It's simply up to the person building in most situations. Building and scaling something people want is a nuanced problem, so we let people use their judgement. When they get it wrong, we are direct and give feedback.

To quote one of our team: "process is scar tissue". It feels natural to implement it when a company starts growing because humans are risk-adverse.

But most people overcorrect by default. That's why large corporations are (in more cases than not) irrationally-obstructive to getting work done.

Should you optimize for speed?

Think hard about what your product should be optimized for before you start making changes.

If you're shipping the latest iPhone, complete design control is more important to your users than having all the features.

Likewise, if you're building a small software product that has better UX than an incumbent, design and control matters.

The most important thing is to figure out if you value speed and autonomy over polish and control. Which path will help you achieve your company's mission better?

We chose speed because:

We raised venture capital (which makes speed easier).

We want to build a multi-product platform.

We’re a late mover in a very competitive sector.

Whichever path you choose, accept there are trade-offs. Just make them consciously.

Good reads for product engineers 📖

8 Reasons Why WhatsApp Was Able to Support 50 Billion Messages a Day With Only 32 Engineers – System Design Newsletter

A perfect example of how small teams can ship huge products.

The most valuable trait of top software engineers – Engineer’s Codex

A great piece from Leonardo Creed on product-minded engineering, inspired by our work on PostHog.

5 ways to improve your product analytics data – Anna Debenham

A quick, actionable guide on how to create a reliable event tracking plan that you (and your data people) won’t hate.

Words by James Hawkins, who uses 👍 unironically.