How to think like a growth engineer

Practical skills all engineers can learn from growth engineers

For the unfamiliar, growth engineers seemingly bounce around the product aimlessly – tweaking signup flows, optimizing onboarding, and running endless experiments (many of which fail).

It's tempting to dismiss this as busywork, but that’s a mistake. Many successful startups have thriving growth teams at their core, driving incremental improvements that accumulate as massive gains.

Growth engineers discover and capture these gains through their unique way of thinking and working. Luckily, you don't need to go to growth engineer school to learn their secrets. It all starts by learning to think like they do – here's how.

1. Become data-driven (for real)

Everyone claims they are data-driven, but it's more than a meme for growth engineers.

Their work comes down to tracking and improving platform or business-level metrics. Our growth team, for example, cares about new revenue, expansion, signup conversion, activation, retention, and more. Their planning, prioritization, and execution focus on improving these metrics.

The tradeoff is caring less about products, features, and user requests. They aren't planning their roadmap months in advance or obsessing about accurate project timelines. They let the metrics be their north star and do whatever, wherever to improve them.

How to start becoming data-driven

Figure out the status quo for the area you work on. To do this:

Define and track your activation and retention numbers. Activation is users reaching the “aha moment” of your product. Retention is them returning to do it again.

Track how they move week over week.

Track how they move with the changes you ship.

You can't think like a growth engineer if you don't have a metrics baseline to start from.

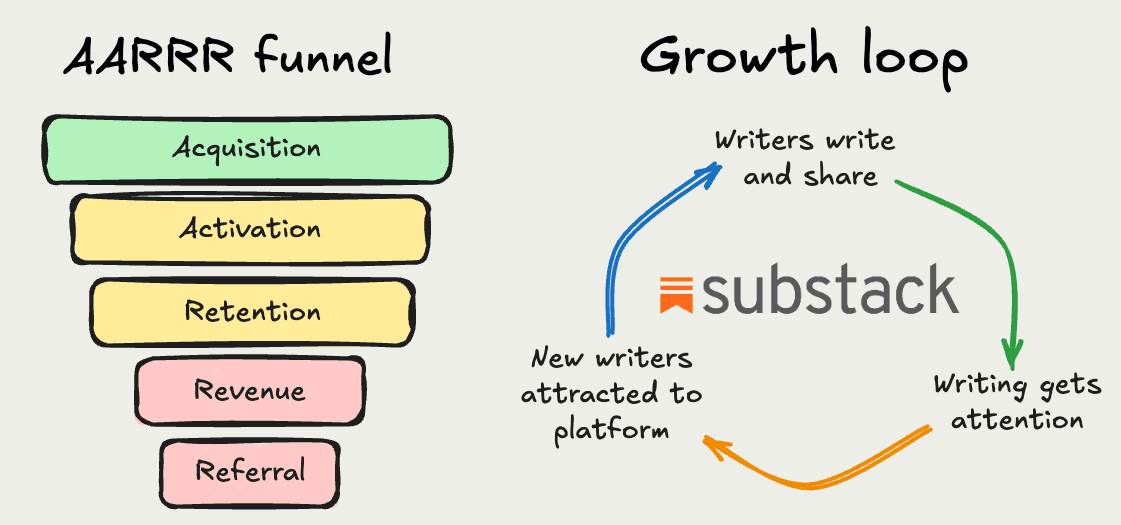

For more advanced users, create a dashboard using a framework like AARRR or growth loops to monitor your key flows.

2. Develop an experimentation mindset

Growth engineers often say "everything is an experiment." This is the elusive "experimentation mindset" that drives them. It differs from the traditional software engineering mindset in a few ways:

Hypothesis over requirements. Software engineers work on features users clearly need. Growth engineers work on more unknowns and care more about exploration and discovery. To do this, they develop hypotheses and run experiments to validate their assumptions.

Iteration over stability. While most engineers focus on developing stable, bug-free code, growth engineers would rather fail fast and iterate. For example, a software engineer might feel uncomfortable adding a dependency before evaluating it, while a growth engineer will ship it to help them test faster.

Pragmatism over perfection. Growth engineers know their experiments might fail and get removed. This means they ship the "good enough" version over the maintainable and scalable one. They know they can always improve it later.

How to start developing an experimentation mindset

Instead of blindly shipping the next feature on your list, think about the hypothesis behind it and the “dumbest” way to test that hypothesis. For example, instead of building out a full feature, run a fake door test to check if users click the option if it’s available.

MasterClass took this approach when testing tiered pricing. As Alexey, their former former head of growth engineering, said:

I knew we needed a dollar estimate, so we created a simple fake door test. Users could select their preferred tier – but at checkout, we let them know they were being upgraded to the best tier and at the cheapest price. In reality, this was the existing one-size-fits-all pricing, and we hadn't actually built any of the functionality to support these new tiers.

This saved us months of engineering time and enabled us to understand how much we could gain if we built this.

3. Prioritize like a growth engineer

Engineers are like bus drivers, helping move a product along its roadmap toward success. Growth engineers are like taxi drivers, bouncing from experiment to experiment stacking little wins.

To understand what their work looks like, let's look at a recent example from our growth team:

Identify a target area. Product analytics has seen some massive upgrades lately and we've also added our data warehouse. Onboarding for both these products hasn't kept up, so they identified this as an area to improve.

Identify a metric that represents that target area. They chose the percentage of new organizations that activate, which combines creating a dashboard, analyzing an insight, inviting a teammate, and more. They wanted to improve this metric while keeping retention the same or improving it.

Create hypotheses. Dashboard templates help teams get value out of PostHog quickly. They hypothesized that adding a dashboard template to the onboarding flow using actions would lead to better activation.

Implement as small of an experiment as reasonably possible. They added a step in the onboarding flow to choose a dashboard template and fill out the variables by creating actions.

How to start prioritizing like a growth engineer

You need to switch from post-hoc analysis to proactive prioritization.

With your target area, metric, and hypothesis in mind, develop a list of experiments to run that can improve your product. Think about how you can test your ideas in the smallest way possible.

For example, if you are trying to improve activation by changing the onboarding flow, could you test removing steps instead of adding new ones?

4. Trust the (experimentation) process

Engineers might see the word "process" and shudder, but being data-driven requires an established process so you can trust the data when making decisions.

When it comes to running experiments, growth engineers always make sure to have:

A sufficiently large sample size of users. This ensures you can hit statistical significance AKA your impact is better than random chance.

A long enough test duration. As a rule of thumb, one week is a good minimum to include the variety of usage across the week. One month is a good maximum to avoid delaying shipping important changes.

A list of common mistakes and how to avoid them. These include only viewing aggregate results, not having a predetermined duration, and neglecting counter metrics.

A way to split and log participants. You want to randomly split test and control groups as well as only log participants in your results. Feature flags help do this.

How to develop a experimentation process

Try it! Set up your feature flags and logging. Craft a hypothesis and goal metric. Check that your sample size is big enough and your duration is long enough.

Going through this process reveals the reality of experimentation. It's not just about shipping changes and seeing what happens, it's a disciplined approach to improvement.

5. Failure is not the end of the world

For a software engineer, failure means bugs, downtime, data corruption, and more nightmare-inducing issues. For growth engineers, it's just another day on the job.

Many experiments fail. Often, a majority of experiments fail. At Google, 80-90% of experiments "fail." You might think of this as a waste of time, but, at scale, 10% of successes can more than pay for all the failures. For example, an A/B test of how Bing displayed headlines boosted revenue by 12% (more than $100M at the time).

On top of the successes, failures are also opportunities to learn. As the saying goes "it's only a failure if you fail to learn." Rapid experimentation, and the gains it provides, are only possible when you embrace failure.

How to get more comfortable with failure

Test both sides of the experiment on yourself first.

Test on a smaller group of users before scaling.

Keep your experiments small so you feel less bad when they fail.

Remember, failure is core to being data-driven (the growth engineer's north star). Lying to yourself about what works and what doesn't will only hurt your product in the long run.

📖 The freshest good reads (since the last ones)

A software engineer's guide to A/B testing – Lior Neu-ner

Lior goes into more depth on how A/B testing works, what makes a good one, how to run and analyze one, and more frequently asked questions.

Debugging conversion problems – Mike Bifulco

Experimentation works for problems big and small. As an example, Mike details his ongoing work to improve newsletter conversion on his personal site.

Pellets not cannonballs: How we experiment at Monzo – Alex Manthei

Monzo, one of the UK’s leading neobanks, details the experimentation process that helped them offer the best possible service.

Statistical Significance on a Shoestring Budget – Alexey Komissarouk

Alexey, former head of growth engineering at MasterClass, guides companies through thinking about their first experiments and how they can run them with minimal traffic.

Words by Ian Vanagas, who is particularly proud of getting a Ronnie Coleman reference into this newsletter. LIGHTWEIGHT BABY!

Nah, that Ronnie Colman poster is hilarious 😂

Great article! I'd argue all engineers need to become a bit more like Growth Engineers—or, more broadly, Product Engineers—owning customer problems end-to-end, being hypothesis-driven, etc. That's one thing AI will never be better at.