The hidden danger of shipping fast

What to do when product velocity breaks the speed of adoption

Is it possible to ship too much – or too fast?

Yes. Probably. Unfortunately.

A handful of people with good judgment and a lot of tokens can now do what used to take a full product org. As a result, software powered by LLMs is cheaper to build and scaling faster than at any point in history.

Once you cross a certain threshold, however, product velocity stops compounding and starts competing with itself. You’re no longer constrained by your capacity to ship new things, but by your users’ capacity to adopt them.

As a company that’s obsessed with shipping fast, we’re acutely familiar with this problem, so I’m sharing how we’re solving it, so you can too.

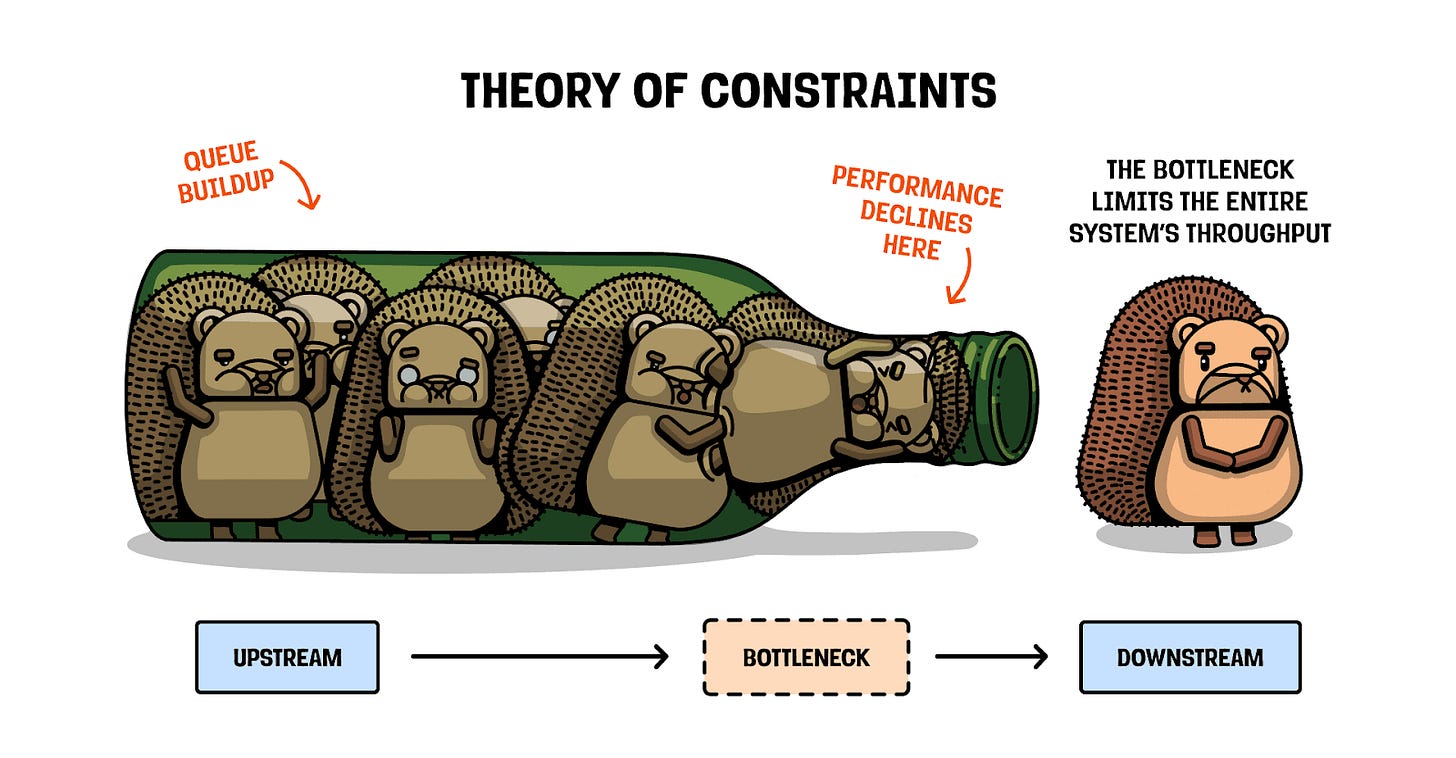

The Theory of Constraints

Since PostHog is a work tool – not a lifestyle brand – even our most enthusiastic users won’t adopt an infinite number of new things per week.

In practice, B2B SaaS users tend to adopt:

One big new thing every few months

A couple of medium improvements

A handful of small quality-of-life upgrades

Everything else gets ignored until someone explains why it matters. This is a classic bottleneck.

Luckily, bottlenecks have solutions. Manufacturers discovered this and crystallized it in a concept called Theory of Constraints (TOC). There’s one principle of TOC that is particularly relevant here:

When upstream output increases without increasing downstream capacity, the system destabilizes.

In our case:

Upstream we have 40+ small teams working asynchronously, shipping at a high velocity, and AI accelerating productivity.

Downstream we have limited user attention, comprehension, and engagement capacity.

Recognizing this, TOC can again help us understand the consequences of this mismatched capacity:

1. Queue buildup

In manufacturing, this looks like excess inventory. In software, this creates an invisible backlog – work that’s finished on your side, but unfinished in terms of user awareness and understanding.

The result is diffuse impact: lots of progress shipped, but less progress felt.

2. Time-to-value increases

As that backlog grows, the gap between production and adoption stretches. Your team keeps shipping code, but each new capability takes longer to move from “available” to “useful.”

Users struggle to keep up with what’s changed. Support and sales spend more time explaining context. Marketing lags releases instead of amplifying them.

3. Quality degradation

When a bottleneck is overloaded, quality degrades through forced tradeoffs.

In software, that shows up as:

Partial adoption instead of full behavior change

Misunderstood capabilities

Features used narrowly when they were designed to be foundational

Your product keeps getting bigger and better, but not proportionally clearer.

Does that mean you should slow down?

Definitely not.

Slowing down is what companies do when they run out of ideas (and clearly that’s not the problem). Fortunately, Theory of Constraints is quite explicit about what not to do here:

Improving non-bottlenecks is a waste of resources. You improve the system by elevating the bottleneck.

Product adoption happens one human at a time, and each individual user has a finite amount of mental bandwidth. So the real question isn’t whether to slow down, it’s this:

How do you elevate adoption without killing velocity?

How to address the real bottleneck of user attention

If you’re building anything serious (and using AI to increase throughput), you’ll hit this wall eventually.

At PostHog, we’re still figuring out the best way around it, but a few points are now painfully obvious.

1. Treat attention like a scarce resource (because it is)

Small autonomous teams naturally optimize for their slice of the product. They own a feature and make it better.

Users don’t experience a product that way. They’re hit with every product change through a finite amount of attention they’re willing to spend.

That mismatch is where things start to break.

What failure looks like:

You treat launches as outputs instead of outcomes.

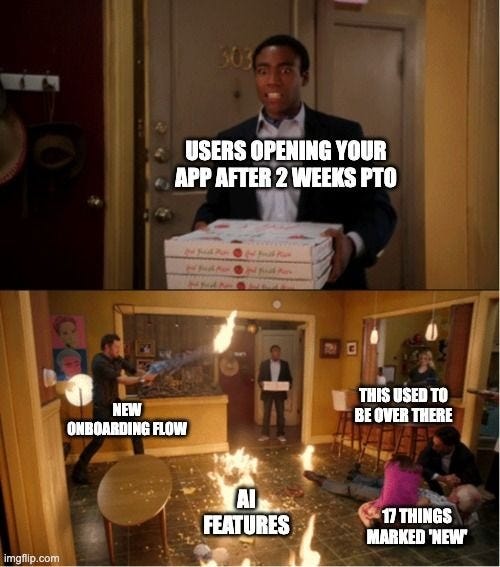

You see this when companies (especially startups) excitedly announce every new feature, and when changelogs or emails become the main way users are expected to keep up.

There’s only a limited amount of attention these methods capture. Ship fast enough and even engaged users will start showing feature fatigue.

If you’ve ever heard “I didn’t know you could do that” from a long-time customer – congratulations, you’ve shipped past the speed of adoption.

Do this instead:

Keep shipping, but be aggressively opinionated about what matters right now.

Not everything needs a launch, a blog post, or to be explained immediately.

Define a launch tier framework such as:

Category definers: New product rollouts or major designs that change how customers think about your category. Require full company alignment. For example, PostHog AI.

Strategic upgrades: Meaningful product improvements (not redefinitions) that don’t require the full machinery of a major campaign. For example, PostHog Logs launch.

Steady improvements: Standard product development that doesn’t require coordination beyond the product team. For example, LLM Analytics adding time to first token.

This is where brand helps. Things like humor, narrative, and deliberate absurdity work because they lower the cost of paying attention. Partnering with influencers that own trust with your ICP is another way to extend mindshare beyond your brand channels.

What this looks like: Notion ships constantly, but markets selectively. Many features land with almost no fanfare, while a small number (AI, databases, templates) get sustained narrative investment over months.

2. Build discovery into the product

If realizing value requires explanation outside of the product, you haven’t removed the adoption bottleneck – you’ve just moved it downstream to marketing, sales, or support.

Users don’t wake up wanting product updates. They’re trying to get something done and move on with their life.

That’s why feature discovery strategically tied to intent works better than announcements that land out of context.

What failure looks like:

Relying on external channels for discovery is brittle. As Andrew Chen argues in Every marketing channel sucks right now, most channels are noisy and saturated. And despite the internet clout you may think it awards, focusing your efforts on Product Hunt, G2, or Hacker News probably isn’t worth the investment.

Your owned channels can easily make things worse. You’ve no doubt been a victim of generic product emails without meaningful segmentation (”why did I receive this?”) or a disruptive in-app experience full of tooltips, banners and popups.

Worst of all are launch videos or press releases that promise “revolutionary” outcomes but don’t clearly explain what changed in the product. Marketing features over benefits is a good pattern breaker, but be warned: too much focus on “what” rather than “now what” makes product adoption someone else’s problem.

Do this instead:

Surface features when they’re relevant to what the user is already doing.

Start by defining clear activation criteria – the signals that indicate a user is engaged with certain parts of your product. Once you discover these signals, you can anchor new features to tasks users already care about.

For example:

When a HubSpot user captures 10+ leads, lead scoring tools gets surfaced

When an Asana user creates a second project, the team invitation flow triggers

When a Zapier user has run multiple successful automations, multi-step templates are emphasized

Another name for this is continuous discovery: letting user behavior and feedback influence what gets amplified next.

Emails and tooltips can help here, but only when they’re contextual: “you’re using X, so Y might be useful.” Better is adding features to existing habit loops, encouraging users to build new habit loops with the features, or making the features sharable.

What this looks like: Atlassian famously struggled with feature sprawl across Jira, Confluence, and their other products. Users couldn’t keep up with so much surface area. The solution wasn’t more marketing, it was investing heavily in in-product discovery, clearer use-case documentation, and opinionated defaults to guide users to success.

3. Measure learning, not just usage

Product adoption isn’t only about feature usage, it’s about helping users get better at their jobs because those features exist. That’s why a lot of our content marketing isn’t really about PostHog at all – it’s about how to become a product engineer.

Sharing knowledge and being helpful builds trust and brand recognition in a way feature announcements never will.

What failure looks like:

When teams get this wrong, they focus on vanity metrics, push product teams toward being a feature factory, and publish content that only makes sense if someone already cares about the product.

One of the biggest mistakes you can make is believing other people care about the product as much as you do.

They don’t.

Do this instead:

What works better is publishing things that are useful even without your product:

Real learnings, like how we built our AI setup wizard

Internal knowledge turned into public artifacts

Honest writeups like postmortems for incidents

Even better, teach the domain you operate in – not just how your product works. Figma, for example, teaches people how to be better designers, not just how to use Figma.

Events are another great tactic to build a community adjacent to your product. For example, Lovable’s SheBuilds hackathon encourages more women to try vibe coding.

What this looks like: HubSpot pioneered inbound marketing by teaching people how to be better marketers before selling them software. For many young professionals, that learning happened years before any purchasing decision – and by then, brand equity was already baked in.

Fast, not frantic

It's tempting to treat “shipping too fast” as a humblebrag, but that’s lazy thinking. If users can’t adopt what you ship, it’s not velocity, it’s waste.

Practically, that means being explicit about what actually deserves attention – and just as explicit about what doesn’t.

So when should you market a specific feature?

It changes a core workflow, not just adds another option

It compounds with an existing behavior (and you can surface it in-context)

It has a clear “aha” moment you can design for

You’re able to support it with docs, onboarding, and follow-up content (not just a blog post)

Everything else should move through the system quietly, without competing for attention it doesn’t need.

Product velocity only compounds when adoption keeps up. If user attention is the bottleneck, your job isn’t to slow down – it’s to be selective. Make a few things loud on purpose, and let the rest be quietly excellent.

Words by Cleo Lant who prefers light mode for most SaaS products (sue me).

🦔 Jobs at PostHog

Want to join a team that’s shipping this fast? We’re hiring:

Agree with Cleo. “Selective” product launches like described in Notion is the way to go. And I also liked the personalized recommendation for particular features depending on product usage and needs.

Great article!

> Does that mean you should slow down?

> Definitely not.

Definitely it does. Overproduction before a bottleneck is waste.

The steps to handling a constraint, from the Theory of Constraints:

1. Identify the constraint (done)

2. Exploit the constraint

3. Subordinate everything else (reduce production upstream)

4. Elevate the constraint (put more people in user education)

5. Repeat with the new constraint